The most misunderstood philosopher?

Add David Chalmers to the list of Berkeley bashers.

David Chalmer’s treatment of Berkeley’s idealism from his latest book, Reality +. (which admittedly only amounts to a few paragraphs upon which I became weirdly fixated).

Full disclosure: Where I stand philosophically

My background:

I’ve had a more classical education—history of Western thought, continental rather than analytic tradition—which didn’t include the more contemporary way of framing things in philosophy. We talked about thought experiments if they happened to come up in the text we were reading, but not in a systematic way. Back then I didn’t encounter the ones that are all rage these days, such as philosophical zombies and Mary’s room and others with cute names.

Also, I learned early on to avoid -isms. But in the blogging world the labels are hard to avoid, even if they cause confusion and misunderstandings. That’s in part why I picked up the Chalmers book. For understanding the current -isms, it has been very helpful.

Where I stand: I generally prefer idealism* to materialism or physicalism. Wherever you pit two philosophies against each other, call them what you will, I’m more likely to side with the one that seems more like idealism.

In philosophy, idealism isn’t about starry-eyed optimism, but instead it refers to a thesis that objects of knowledge are in some way dependent on the activity of mind.

But this may be too broad a definition (as you’ll see in the video if you click on ‘idealism’ above). Immanuel Kant’s* philosophy is confusingly known as transcendental idealism and while he did think objects of knowledge are dependent on the activity of the mind, he also believed there was…something?… beyond our knowledge, a realm of “things in themselves”, which he referred to as noumena.

According to Kant, we can’t know or say anything about noumena, and yet noumena are taken to be the cause of the phenomena we perceive.

Things known/perceived: phenomena

Things unknown and unknowable: noumena

Chalmers declares himself something of a Kantian on just this point:

“There’s an interesting mapping from our picture to Kant’s. The structure of reality corresponds to Kant’s knowable realm of appearances. Whatever underlies this structure corresponds to Kant’s unknowable things in themselves.” Ch 22: Is reality a mathematical structure? See the section called “Kantian humility”.

My problem with this is, how can we assume an underlying reality causes phenomena when we not only don’t know, but can’t know, anything about it? What purpose does an unknowable realm of “things in themselves” serve? How can science claim to make progress in obtaining knowledge about reality (assuming that means ‘things in themselves’) when it can’t, not even in principle, know what it’s progressing towards?

Chalmer’s epistemic structural realism doesn’t seem to me to address this problem better than ordinary scientific realism. Enduring mathematical structures that can never describe ‘intrinsic’ reality can never bridge the gap. ESR only adds another layer of mystery to the problem of what it is science is supposed to be getting closer to knowing. We’re left with the question: What are the mathematical structures structures of?

(For an explanation on types of structuralism and other -isms, see this blog post at SelfAwarePatterns.)

Bishop George Berkeley eliminates the problem by eliminating noumena.

“In the last place, you will say, what if we give up the cause of material Substance, and stand to it that Matter is an unknown somewhat- neither substance nor accident, spirit nor idea, inert, thoughtless, indivisible, immovable, unextended, existing in no place. For, say you, whatever may be urged against substance or occasion, or any other positive or relative notion of Matter, hath no place at all, so long as this negative definition of Matter is adhered to. I answer, you may, if so it shall seem good, use the word "Matter" in the same sense as other men use "nothing," and so make those terms convertible in your style. For, after all, this is what appears to me to be the result of that definition… I do not find that there is any kind of effect or impression made on my mind different from what is excited by the term nothing.” (Principles of Human Knowledge, §80.)

What makes Berkeley important to the history of philosophy are not his arguments for the existence of God, which weren’t novel, but his denial of Matter.

* I think Husserl’s phenomenological bracketing of the natural attitude is the fairest way to deal with this problem, but if you don’t know what I’m talking about, that’s okay.

* For the record, some of you may be surprised to hear that Plato wasn’t my first love. It was actually Kant. He’s the reason I transferred to a college across the country; I wanted to take a class dedicated to the Critique of Pure Reason. I even pretended I had read Hume to get into the class. “Hume said…that stuff about causality? Like, there’s not really a necessary connexion between one event followed by another? And so, like, we don’t really know if the sun is gonna rise tomorrow?”

Don’t get me wrong, I like Chalmers, which makes it all the more surprising that he mischaracterizes Berkeley’s idealism:

“In Western philosophy, idealism is most closely associated with the 18th-century Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley. In his 1710 book A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, Berkeley put forward his famous slogan, esse is percipi. To be is to be perceived. A spoon exists if it is perceived. This means roughly that if a spoon appears to you, then the spoon is real. To put it another way, appearance is reality. The thesis bridges the gap between the mind and the world by saying there is no gap.” (Ch 4. Can we prove there is an external world?)

Whoawhoawhoawhoawhoa. Appearance is reality?

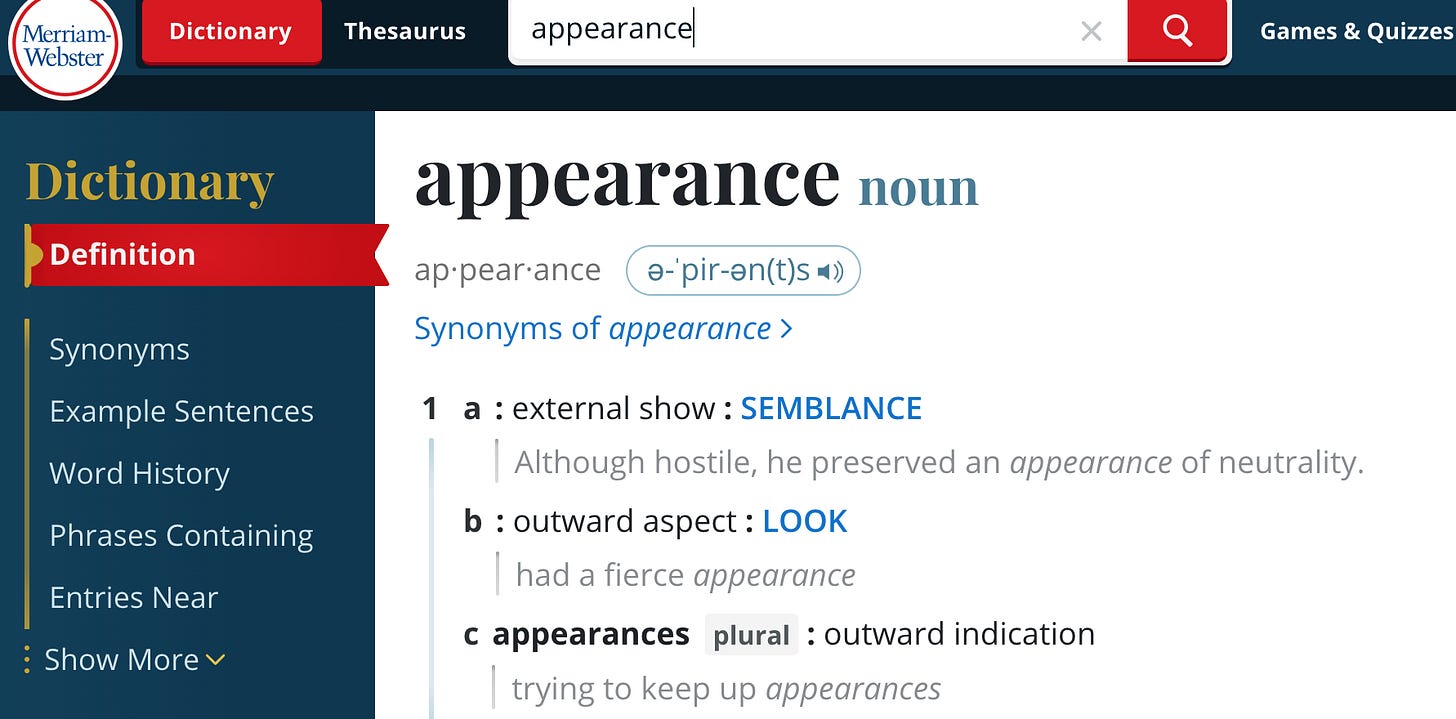

Chalmers takes Berkeley’s neutral term, perceive, and replaces it with a loaded synonym that connotes the opposite of what Berkeley intended. Consider the first definition of appearance below:

Appearance implies there is some reality under the surface. This is precisely what Berkeley wants to deny!

Berkeley:

“Colour, figure, motion, extension, and the like, considered only as so many sensations in the mind, are perfectly known, there being nothing in them which is not perceived. But, if they are looked on as notes or images, referred to things or archetypes existing without the mind, then are we involved all in scepticism. We see only the appearances, and not the real qualities of things.” Principles of Human Knowledge, §87 (My emphasis)

“For as to what is said of the absolute existence of unthinking things without any relation to their being perceived, that seems perfectly unintelligible. Their esse is percipi, nor is it possible they should have any existence out of the minds or thinking things which perceive them. §3-4

“The only thing whose existence we deny is that which philosophers call Matter or corporeal substance. And in doing of this there is no damage done to the rest of mankind, who, I dare say, will never miss it.”§35.

Berkeley objects to un-perceivable absolute existence, which he identifies as Matter. He considers Matter an “abstract idea” that has no grounding in experience. As we’ve seen, I take Berkeley’s Matter as basically equivalent to Kantian noumena, or “things in themselves”, though Kant came a bit later in the historical timeline.

After reading Chalmers I felt the need to defend Berkeley, but then I thought it might be fun to let Berkeley answer for himself.

A dialogue between Chalmers and Berkeley, in their own words

Note: Berkeley uses the word “idea” to mean “things”. Somewhere in his book he admits this is a strange use of the word and explains he doesn’t really care if you prefer to say “things” so long as you understand what he means, but I can’t find where he said this. Sorry.

Chalmers:

“There are a lot of objections to idealism. One objection is “Whose minds is reality made of?” If it’s my mind alone, then we have solipsism: I’m the only one who truly exists—or, at least, it’s my mind that makes up the universe. That way megalomania looms.” Ibid.

Berkeley:

“Wherever bodies are said to have no existence without the mind, I would not be understood to mean this or that particular mind, but all minds whatsoever. It does not therefore follow from the foregoing Principles that bodies are annihilated and created every moment, or exist not at all during the intervals between our perception of them.” §48.

Chalmers:

“As with Descartes, God comes to the rescue. As long as God is always watching the whole world, unobserved reality is not a problem. God’s experiences sustain the ongoing reality. Our own experiences derive from God’s experiences. The constancy of God’s experience explains why we always see the tree when we return to the quad.” Ibid.

Berkeley:

“… all those bodies which compose the mighty frame of the world, have not any subsistence without a mind…consequently so long as they are not actually perceived by me, or do not exist in my mind or that of any other created spirit, they must either have no existence at all, or else subsist in the mind of some Eternal Spirit- it being perfectly unintelligible, and involving all the absurdity of abstraction, to attribute to any single part of them an existence independent of a spirit.” §3-4. (my emphasis)

Chalmers:

“Another serious objection: What about unobserved bits of reality? For example, what happens when I leave the room?” Ibid.

Berkeley (rolls eyes):

“The table I write on I say exists, that is, I see and feel it; and if I were out of my study I should say it existed- meaning thereby that if I was in my study I might perceive it, or that some other spirit actually does perceive it. There was an odour, that is, it was smelt; there was a sound, that is, it was heard; a colour or figure, and it was perceived by sight or touch. This is all that I can understand by these and the like expressions.” §3.

Chalmers:

“What about parts of the universe were there are no observers, and times long ago, before consciousness evolved? Is there any reality there?” Ibid.

Berkeley:

“…you will say there have been a great many things explained by matter and motion; take away these and you destroy the whole corpuscular philosophy, and undermine those mechanical principles which have been applied with so much success to account for the phenomena. In short, whatever advances have been made, either by ancient or modern philosophers, in the study of nature do all proceed on the supposition that corporeal substance or Matter doth really exist. To this I answer that there is not any one phenomenon explained on that supposition which may not as well be explained without it, as might easily be made appear by an induction of particulars. To explain the phenomena, is all one as to shew why, upon such and such occasions, we are affected with such and such ideas. But how Matter should operate on a Spirit, or produce any idea in it, is what no philosopher will pretend to explain; it is therefore evident there can be no use of Matter in natural philosophy. Besides, they who attempt to account for things do it not by corporeal substance, but by figure, motion, and other qualities, which are in truth no more than mere ideas, and, therefore, cannot be the cause of anything, as hath been already shewn.” (§50.)

Chalmers:

“The underlying problem for idealism is that in order to explain the regularities of our appearances (the fact that we see an identical tree day after day, say) we need to postulate some reality that lies beyond these appearances and sustains them.” Ibid.

Berkeley:

“Let us examine a little the description that is here given us of matter. It neither acts, nor perceives, nor is perceived; for this is all that is meant by saying it is an inert, senseless, unknown substance; which is a definition entirely made up of negatives, excepting only the relative notion of its standing under or supporting. But then it must be observed that it supports nothing at all, and how nearly this comes to the description of a nonentity I desire may be considered.” §68. (my emphasis)

Chalmers:

We create a rich simulated world, with a simulation of George Berkeley inside it. Sim Berkeley tells us, “Appearance is reality.” Since there is no appearance of a simulation, there is, in actuality, no simulation. Sim Berkeley concludes, “I am not in a simulation. My experiences are all ideas produced by ideas in God’s mind.”

From our perspective, Sim Berkeley looks a bit ridiculous. He says he’s not in a simulation, but he is wrong. He is in a simulation. He says that appearance is reality, but there is a vast realm of reality beyond what appears to him. (Ch 4. Can we prove there is an external world?)

Berkeley:

Let us examine at once the foregoing experiment of thought: THE ETERNAL INVISIBLE MIND, being entirely devoid of unknowable substance, contemplates a wholly immaterial universe which doth sustain the spirit of David Chalmers. But Chalmers, convinced by his own extravagances of abstract thought, contends in the name of Kantian humility that there must exist an unknowable substance perceived by no mind whatsoever.

To the All-Sufficient Spirit, our venerable Chalmers looks ridiculous. He postulates the existence of an unknowable substance apart from all minds, but he is wrong, for he is himself a spirit belonging to a complete, wholly immaterial world. (Okay, maybe Berkeley didn’t say this. But you get the point.)

I want to say I’m not as hostile to the concept of noumena as I probably seem. I just felt like sticking up for Berkeley, who was misunderstood and mischaracterized even while he was alive. His legacy in history of philosophy need not be shat upon today.

What do you think?

What do you think of noumena, or ‘things in themselves’? Knowable? Or no? If not, does believing in noumena serve some function, maybe as a placeholder, in your system of belief?

What philosophy do you find most convincing or appealing?

As always, feel free to comment, even if just to say, “Hey.”

All Chalmer’s quotes taken from his latest book, Reality +: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy.

All Berkeley quotes taken from A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (this link is to the entire book which you can read for free)

As a physicalist / materialist philosopher, I'd like to share how I think about these questions of yours:

--> My problem with this is, how can we assume an underlying reality causes phenomena when we not only don’t know, but can’t know, anything about it? What purpose does an unknowable realm of “things in themselves” serve? How can science claim to make progress in obtaining knowledge about reality (assuming that means ‘things in themselves’) when it can’t, not even in principle, know what it’s progressing towards?

I recently read your and your husband's "Truth and Generosity after you let us know it was available for a cheap price. (Thank you!) And I think some of the answers to your questions can be gleaned from that. I would say that a major point from T&G is that the production of knowledge is inherently social. The best argument I've heard against Idealism is that it would make the social project of science impossible. Social knowledge wouldn't come together. And scientific hypotheses would never be disconfirmed. But this all happens precisely because there does seem to be an objective physical reality "out there" which corrects our mistaken notions all the time. Without this objective reality, what would we all be taking about? Yes, we can never be certain of that or know it objectively because we only have our subjective inputs to use for evaluation of the world. And we can't know the future and what disconfirming evidence may arrive someday. But we can make the hypothesis that a single physical universe exists for us, and so far that hypothesis hasn't been disproven by new evidence.

That's quite a different stance than just "assuming an underlying reality". It acknowledges that life started its knowledge journey in absolute ignorance. Living organisms have had to make guesses, check them, and refine them based on feedback. Over the eons of this, life has reached a pretty broad consensus that there is an objective reality that we all share. How else could we communicate and exist with one another??

When you ask "How can science claim to make progress in obtaining knowledge about reality (assuming that means ‘things in themselves’) when it can’t, not even in principle, know what it’s progressing towards?" — the answer is that we claim to make progress in generating broad consensus about things. That's the best we can do. That's the answer Naomi Oreskes gave to the title question of her book "Why Trust Science?" We are progressing towards a shared understanding of how the world works. That's never going to give us a rock solid undoubtable foundation of knowledge (sorry Descartes!), but that's the situation we seem to be in and that's perfectly acceptable to me and other pragmatically-minded philosophers.

A friend of mine just posted some "short philosophy jokes" on his website. I had to share the final one here:

Overheard in 18th century England: “Did you hear that George Berkeley died? His girlfriend stopped seeing him.”

: ) Full post here for some other chuckles:

https://reasonandmeaning.com/2024/02/14/short-philosophy-jokes/