Music in this podcast episode comes from the album Spirit Vine Tea, by Nick Herman. Check out his music, support indie artists!

I tend to think in classical terms about issues in philosophy of mind. When someone says “dualism”, I default to: how does mind interact with matter? But thinking in these terms in today’s context is kind of like watching a 3D movie without the 3D glasses. No wonder everything looks weird.

WHAT IS PHYSICALISM?

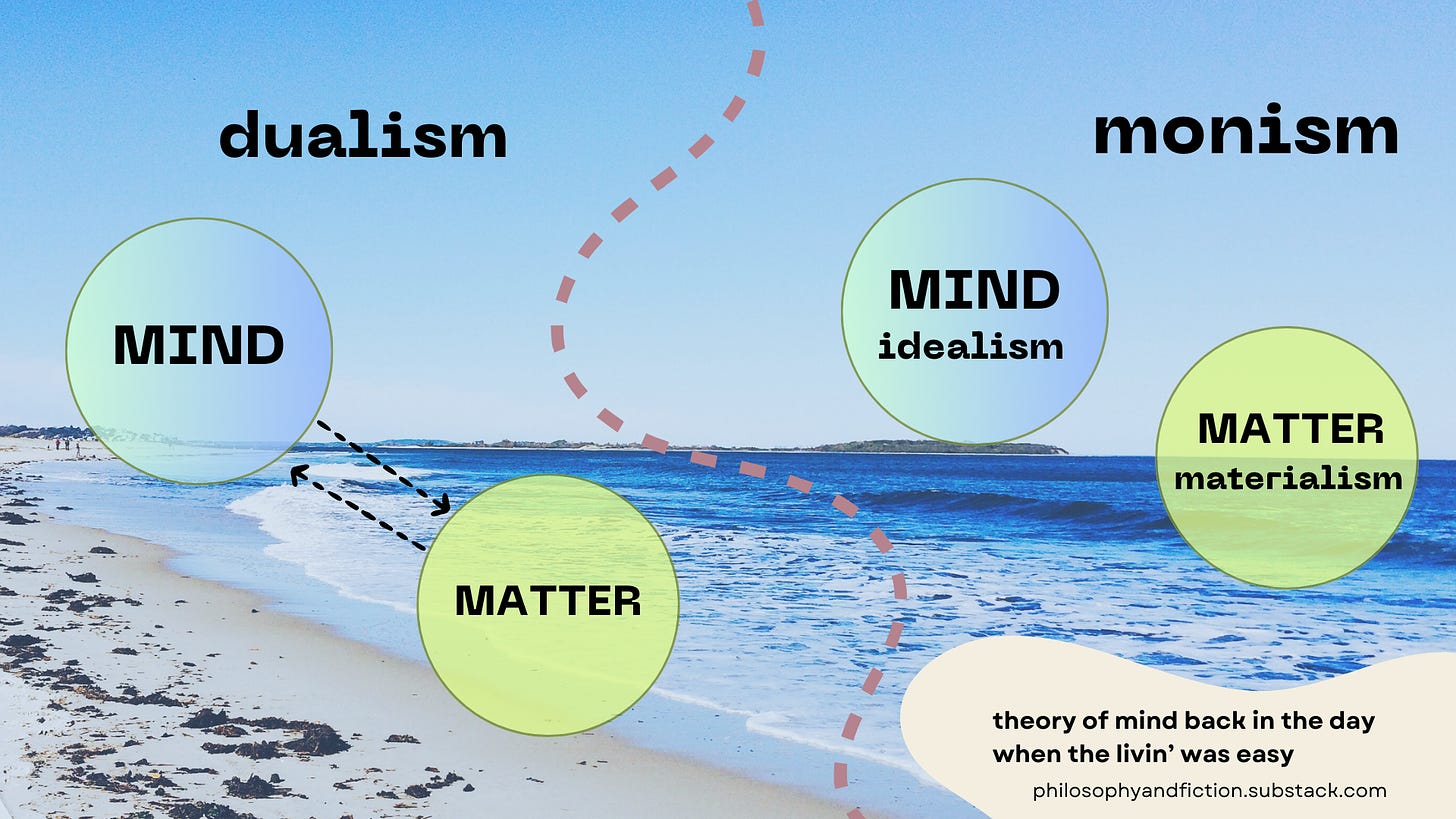

The 3D glasses in this case represent physicalism, which often gets described as the belief that ‘there is nothing over and above the physical’, or that ‘everything supervenes on the physical’.1 As far as I can tell, physical sometimes means objects as they appear to us, such as when people talk about trees and lollipops and other tangible things, but other times it refers to an underlying conceptual structure such as information or mathematical-scientific laws (which I still think of as ideas)2, or both levels at once. I think it’s safe to say physicalists take the scientific investigation into the nature of reality, however that is understood, as fundamentally correct. This is vague, unfortunately, but physicalism means different things to different people. Maybe it’s best characterized as an attitude, a belief that science gets things basically right.3

Whatever form it takes, physicalism often gets imported, sometimes quietly, into many stances on consciousness, even panpsychist theories, making it a default position for our times. There’s a sense that one need not even mention the physicalist premise, since it is, supposedly, as obvious as air.

I don’t think it’s obvious, though I realize many of you do. I hope you will nevertheless find my questioning of this position worthwhile, even if only to see what it means for some of our contemporary theories of mind, particularly property dualism.

DUALING DUALISMS

Whatever form it takes, dualism can’t be expected to be satisfying, but that doesn’t mean all dualisms are equally dissatisfying. I would argue that property dualism, by aligning itself to physicalism, introduces new problems beyond the classic version.

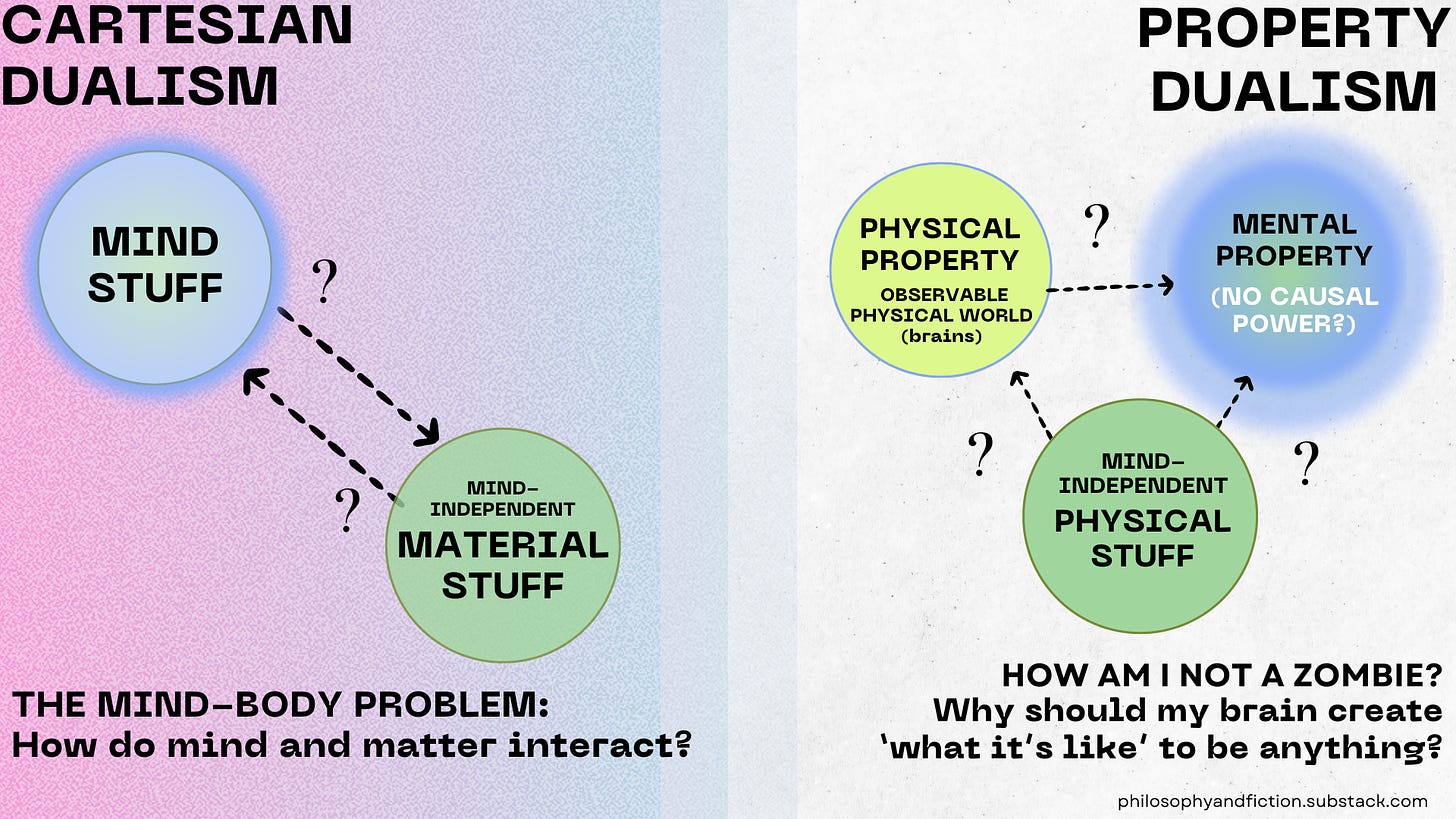

The traditional Cartesian mind-body problem known as substance dualism asks how an immaterial substance can interact with a mind-independent material substance. I won’t discuss Cartesian substance dualism in detail here, but you won’t need more than the image above to understand this post. If you want to find out more, you can download my thesis on Plato and Descartes from this page. In it you’ll find my analysis of the Metaphysical Meditations.

Property dualism asks how a brain or the functional equivalent can generate what we now call consciousness. The dualism here is between two properties, not substances. These properties, the mental and the physical, both arise from the same mind-independent physical reality.

PROPERTY DUALISM IS BASICALLY PHYSICALIST

Property dualism is often discussed as being in opposition to physicalism because it acknowledges that the phenomenal qualities we experience are real, not illusory byproducts of the brain, and this, it is so often said, poses a hard problem. I don’t hear much of anything about how it aligns with a physicalist conception of the world, but it does.4

Farewell immortality of the soul! Property dualism replaces ‘mind-substance’ with ‘mental properties’ to avoid any implication of immortal souls and spooky ghosts in the machine. You’ve probably already guessed as much. But contrary to what I first thought, doing away with mind-substance is more than just semantics; it changes the fundamental nature of the problem, as we’ll soon see.

Incidentally, these days we talk about consciousness, not minds. I think that’s an unfortunate change since ‘consciousness’ can also refer to levels of consciousness, such as the difference between being fully awake and being unconscious, and that can create confusion. But I digress.

Consciousness must ‘supervene on’ the physical. In other words, the mental depends on the physical in some way or another—this ‘in some way or another’ is what most of the current debate is about. Regardless of the details, this relationship implies an emergent consciousness out of a fundamental physical reality. To me, the word ‘emergent’ conjures wispy soul-like apparitions rising from dead matter like smoke, but here ‘emergence’ just means physical properties cause mental properties somehow and yet are not reducible to them, at least not without destroying what they essentially are. Therein lies the so-called hard problem:

“Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does. ”

—David Chalmers, Facing up to the Hard Problem of Consciousness.

If what you have in mind is the classic mind-body problem, this question wouldn’t seem especially odd. It’s just stating one part of the problem. But what you might not notice is that no one is asking, “How can a rich inner life be accompanied by physical processing?” For property dualism, the elimination of mind-substance supposedly does away with the need to ask the question.

But it seems we’ve merely moved half of the interaction problem up a level: how do physical properties interact with mental properties? Keep in mind, we haven’t solved the reverse question, we’ve simply dismissed it. And this one-way interaction problem rests on top of the problem of how the two properties arise from a common physical reality. Classic dualism is starting look svelte by comparison! Not only have we added ugly epicycles, we’ve also decreased the potential explanatory power of the theory as whole with this supposed upgrade. And that’s precisely because property dualism refuses to face the whole hard problem.

PROPERTY DUALISM IGNORES OUR CAUSAL AGENCY.

Because the physical is taken to be fundamental, its laws, whatever they are, apply universally. This means consciousness, being dependent ‘in some way or another’ on the physical, is most likely not causally efficacious. I say ‘most likely’ because whether we have agency depends on which scientific theory is in favor at a given moment, whether the principles of quantum mechanics upturn classic determinism. Until then, determinism seems to be the default, which means causality is a one-way street: mind cannot cause anything. Chalmers only glances furtively at this strange situation in his ‘Facing up to the Hard Problem’ paper:

“We might say that phenomenal properties are the internal aspect of information. This could answer a concern about the causal relevance of experience—a natural worry, given a picture on which the physical domain is causally closed, and on which experience is supplementary to the physical. The informational view allows us to understand how experience might have a subtle kind of causal relevance in virtue of its status as the intrinsic nature of the physical. This metaphysical speculation is probably best ignored for the purposes of developing a scientific theory, but in addressing some philosophical issues it is quite suggestive.”

A subtle causal relevance indeed! What on earth is this ‘internal aspect of information’? This strikes me as a verbal sleight of hand.

The fact is, we don’t experience ourselves as non-agents. Strapping inefficacious ‘properties’ onto billiard balls blindly bouncing around in a causally-closed deterministic universe won’t do the trick. And if it’s later decided that quantum mechanics makes the physical world fundamentally uncertain, that merely straps consciousness onto billiard balls that may or may not go poof.

More to the point, there’s a problem with the theory’s internal consistency. How can we take our phenomenal experiences as unassailably given, but not our intentions? Why one and not the other? This distinction seems arbitrary even if you believe facts can only be established extrinsically, for it looks like a halfhearted attempt to side with physicalism that doesn’t go far enough. But if you take intrinsic givens to be perfectly legitimate, or even most legitimate (as I do), accepting the rich inner life while leaving lived agency in the lurch makes zero sense.

Phenomenologically—experientially—my lived agency belongs essentially to my conscious experience. From the intrinsic perspective this can’t be an illusory byproduct, as it’s buried deep in the basic structure of how I experience. Determinism isn’t merely perplexing or counter intuitive, it can only make sense in theory, from a god’s eye view. Even those physicalists who seem to enjoy flying in the face of common sense will readily admit determinism is a real problem, or at least something they must accord with our own lives as moral agents. But while determinism threatens responsibility on a social scale, it fundamentally undermines the very possibility of experience as it is experienced. In its experiential form, agency is intentionality, and intentionality is an essential feature of conscious experience.

Intentionality is a word that gets tossed around a lot and it has consequently become watered down to mean just about anything, but I’m thinking of the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl when I use the term. In this sense, intentionality is the experienced directed-ness of my awareness against an indeterminate background, the totality of which we call the world. At the highest level, there is always an “I” doing the experiencing, or if you prefer something more Zen, call it the unity of consciousness. There may be other essential features to consciousness besides these, but at a minimum there is no conscious experience without intentional agency. Intentional agency lies at the heart of conscious experience; for it, determinism is inconceivable.

THE EFFECT OF PHYSICALISM ON OTHER ‘-ISMS’

Let’s take a look at some alternatives to property dualism that also assume physicalism:

Elimination or reduction. Take it neat. Experiential qualities are, like the feeling of mental causation, nothing more than the brain or equivalent functions thereof. Period. End of story. These theories get high marks for elegance, but that elegance comes at a steep price. This response doesn’t solve anything by ducking the question.

Property dualism adds epicycles…so let’s add more! Reintroduce mental agency at the ‘property’ level, perhaps with a question mark, give your theory a confusing name that sounds like the opposite of what it is, then let everyone raise a big stink over “overdetermination” (according to physicalism, events can only have one cause; if an event has more than one cause, it’s charged with the great sin of “overdetermination”).

Physicalist panpsychism.5 Introduce ‘mind stuff’ into the very fabric of the physical world. What we need are mini-qualities that ‘live’ within the causally-effective layer of physical stuff. But again, there’s the assumption that we lack agency at the heart of this view, which means mind stuff can’t inherit the causal efficacy of its physical correlates.6

Are there others? Am I leaving something out? Please tell me there is no such thing as physicalist idealism. Please.

THE WINNING PHYSICALIST THEORY (FOR ME) IS…

If I had to be a physicalist I suppose panpsychism would have more appeal for me. Besides, I just love this passage from Strawson’s paper:

‘They are prepared to deny the existence of experience.’ At this we should stop and wonder. I think we should feel very sober, and a little afraid, at the power of human credulity, the capacity of human minds to be gripped by theory, by faith. For this particular denial is the strangest thing that has ever happened in the whole history of human thought, not just the whole history of philosophy. It falls, unfortunately, to philosophy, not religion, to reveal the deepest woo-woo of the human mind.

—Galen Strawson, Realistic Monism Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism

And yet, despite all the common sense that physicalist panpsychism purports to save, it, too, fails to account for the most basic and fundamental aspect of our experience—our agency. Keep in mind, I’m not saying we have complete control over all of our actions, for that would ignore the complexity of our psychology. And I’m also not saying that determinism is false in the grand scheme of things; I’m being agnostic on that.7 What I’m talking about is an inconsistency in validating one kind of intrinsic fact, but not the more fundamental fact of causal agency—I say “finger, move” and guess what? It moves! I go into the kitchen to get myself an ice cream cone. Why?

. . .

No! Not because billiard balls made me do it!

I did it because I wanted an ice cream cone and so I got over my laziness and went into the kitchen to make myself one. (Classic vanilla in case you were wondering. I know, surprise surprise.)

To deny this everyday experience of agency or mental causation is the strangest thing that has ever happened in the whole history of human thought, not just the whole history of philosophy, and it reveals the deepest woo-woo of the human mind. So say I. Besides, any theory of mind that can’t take a desire for ice cream as the cause for my getting off the couch is no theory of mind for me.

WHO WINS THE DUALISM DUEL?

I can’t see property dualism as a win over classic dualism. We still have the problem of how mental properties ‘emerge’ from physical ones like brains (or equivalent). We might think we score a point over classic dualism in not explaining why experience should be accompanied by physical activity, but alas, our dodge brings with it even worse problems, as described above.

On top of that, property dualism—or really, epiphenomenalism, because that’s what we’re dealing with here guys—introduces complications that I didn’t talk about, like how do physical properties arise from mind-independent reality? Even worse, how do mental properties arise from a mind-independent reality? Or do they arise from a mind-dependent reality that’s dependent somehow on a mind-independent reality? Epicycles!

Not only has property dualism imported the physicalist assumption for no reason except to appeal to the scientifically-inclined, it has hawked a big fat loogie in the face of common sense to boot. I think it’s our causal agency that should be taken as given. A theory of mind should account for experience as it is experienced.

What do YOU think?

Do you think a theory of mind should ‘save the experiences’? If not, why not? As always, feel free to comment on anything.

Many thanks to Nick Herman for his brilliant music, to Suzi Travis for your lively discussions, and to SelfAwarePatterns for getting me to put on squint through the 3D glasses for a sec, at least for long enough to write this post.

In other words, physicalism is a form of substance monism, there is only one kind of stuff in the world, and it’s physical.

These notions of the physical can be seen to be at odds with each other, and it’s not clear to me how either version can be considered mind-independent, but I have a post about this coming up so I won’t say more here.

There are problems with taking science to be the final word on reality. Are we to take our current scientific theories as our standard to which all else must conform? But we once thought the sun revolved around the earth, so how do we know our current theories are right? Maybe we take some complete, perfected science as bedrock. But what would that be? It’s hard to wrap our minds around the notion of a completed science, since that contradicts the inductive nature of empirical inquiry which is said to lie at the heart of what science is. In other words, I may know everything there is to know about the laws of nature from the beginning of time up to the present, but tomorrow a new fact could change everything. As your financial advisor might say, past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is the nature of science to be contingent, ongoing. But then if we can’t grasp completed science, not even in principle, how can we know where it’s going? How can we know we’re making progress towards understanding reality? Isn’t scientific progress merely an unsupported assumption, then? This is just to brush on some of the concerns you can find in debates on scientific realism and anti-realism.

Here’s David Chalmers explaining why property dualism is “often held to be more compatible with a scientific worldview”:

At 9:54 Chalmers states that a version of the interaction problem we find in Descartes’ substance dualism re-arises in property dualism. He goes on to state, “property dualism leads to epiphenomenalism: the mind has no effect on the physical world.”

If you’re scratching your head over what physicalist-panpsychism even means, I was too when I first heard about it in Galen Strawson’s famous paper. Everything turns on what Strawson means by ‘physical’ :

“Real physicalism, then, must accept that experiential phenomena are physical phenomena. But how can experiential phenomena be physical phenomena? Many take this claim to be profoundly problematic (this is the ‘mind–body problem’). This is usually because they think they know a lot about the nature of the physical. They take the idea that the experiential is physical to be profoundly problematic given what we know about the nature of the physical…”

—Galen Strawson, Realistic Monism Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism

I find it hard to understand what he’s saying, but my guess is: Materialism is no longer about matter, no longer about billiard balls bouncing around. The physical turns out not to be ‘stuff’, and the closer we look, the more mysterious it seems. If the line between the physical and the experiential has been blurred by quantum mechanics and other paradoxical scientific theories, why can’t phenomenal consciousness be physical too?

I totally agree with him that we don’t know what we’re talking about when it comes to the physical, but I think we should probably try to sort it out, even if just for the sake of avoiding equivocation and confusion. This, however, is a long discussion which I’ll have to save for another day.

Strawson’s not the only one taking up the physicalist-panpsychist position:

“My proposed framework is a type of physicalism, which is itself a type of monism.”

—Tam Hunt, “Kicking the Psychophysical Laws into Gear: A New Approach to the Combination Problem”.

That said, I’m also seeing a proliferation of panpsychist theories ranging from ‘physicalist’ to ‘idealist’—those of you who know me know which one I prefer. Here’s someone who apparently agrees with me:

“Meixner distinguishes four versions of panpsychism based on their dualist or idealist and atomistic or holistic nature (of which the dualist versions work no better than simple dualism for the mind/body problem, and the atomistic versions suffer from the combination problem). Idealism is accordingly often treated as some form of idealist panpsychism, but I think this is misguided: Panpsychism is essentially based on the same notions of space and passive mental causality as materialism, while idealism implies emergence of space and real agency…”

—Martin Korth, Towards a scientifically tenable description of objective idealism

It seems for every theory of mind, there’s a shadow panpsychist version. It’s panpsychism everywhere!

“There may be all sorts of other factors affecting and changing you. Determinism may be false: some changes in the way you are may come about as a result of the influence of indeterministic or random factors. But you obviously can’t be responsible for the effects of any random factors, so they can’t help you to become ultimately morally responsible for how you are.

Some people think that quantum mechanics shows that determinism is false, and so holds out a hope that we can be ultimately responsible for what we do. But even if quantum mechanics had shown that determinism is false (it hasn’t), the question would remain: how can indeterminism, objective randomness, help in any way whatever to make you responsible for your actions? The answer to this question is easy. It can’t.”

Here, Strawson seems to think the question must be answered by reference to the extrinsic, or scientific, worldview. But why?

The quote at the end of the article by Ian McEwan points to the more fundamental sense of agency, but even that is merely surface level compared to the degree of experiential entanglement I’m trying to get across here.

Agnostic…for now. :)

Share this post